Menu

9 most common mistakes when creating sustainable packaging

Society’s attention toward sustainability is constantly growing, and lawmakers are taking more concrete steps to define sustainability and prevent instances of consumers being misled in that regard. These changes directly affect the packaging industry, which has been experiencing many changes dues to sustainability. Brands are refining their packaging more actively: changing materials, educating consumers, participating in recycling programs, minimizing the use of raw materials and energy, testing reusable models, and even ditching packaging entirely. The impact is already evident – the old linear economic model “take – make – dispose” is slowly disappearing, making way for more viable solutions. However, this transformation is still littered with mistakes that, contrary to popular belief, can even increase pollution, distort the concept of sustainability in the eyes of consumers, and make the lives of those true proponents and creators of sustainability much more difficult. This article will overview the most common sustainability mistakes businesses make.

1. Unclear labeling and confused consumers

1. Unclear labeling and confused consumers

Responsible consumers are voicing their displeasure with packaging that claims to be “recyclable and/or compostable” when there is no indication on how to do so after use. Sometimes the material of such packaging looks and feels natural as if made from paper fiber, but it also has the water and oil repellent properties of plastic. If we look at food packaging, it is common for it to be stained and soiled, which begs the question: should it be disposed of among paper, plastic, or common garbage, and is it even recyclable? Does your packaging create these dilemmas for consumers? To answer this question, it’s essential to communicate with consumers who have no idea about the changes made to your packaging solutions but who can objectively ask questions about the packaging in their hands. Answers to these naturally occurring questions should be placed on the packaging itself. More detailed explanations can be addressed through other channels: in the physical location or a digital website, or on social media. There is little use for a good packaging solution when the means of disposal aren’t clear to consumers. It can even have damaging consequences – improperly sorted packaging could soil and stain properly sorted and recycling-ready waste.

2. What is the actual CO2 footprint?

2. What is the actual CO2 footprint?

Did you know that if we were to compare packaging made from PET plastic, aluminum, and glass – the former would account for the most significant CO2 footprint? Based on this criteria, a glass container produces 5 times more CO2 than a plastic PET bottle, aluminum leaves 2 times more CO2 than that same plastic bottle. These results are due to the manufacturing process and transportation. Does this mean we should only choose plastic while leaving aluminum and glass aside? Certainly not. Today, less than 9% of plastic packaging is recycled, the oceans are full of it, and it requires manufacturing fossil fuels. On the other hand, aluminum and glass can be continually recycled and returned to circulation repeatedly. One particular bottle deposit system in Lithuania goes through 50mm. single-use (the packaging is broken and transported to be recycled into new packaging) and around 59mm. reusable (returned to the drink manufacturers) glass containers. This means that more than half of all containers in the bottle deposit system are in circulation. The CO2 footprint left behind can eventually become equal to that of plastic manufacturing by reusing glass containers. All these numbers remind us that when creating packaging, choices must be made objectively and different perspectives should be considered. In the plastic, aluminum and glass examples mentioned earlier only global averages were provided, which can differ based on the distances between the sourced raw materials, package manufacturing, retail location, packaging disposal location, manufacturing process, energy use, and other parts essential to the operation. So even if a more CO2-friendly package seems ideal for both the client and the product, there should be no rush to change the entire process and risk losing the system’s benefits: safety, convenience, and hygiene. It is most beneficial, to begin with a detailed analysis of the current system and its alternatives. Perhaps there is a possibility of buying raw materials from a closer location and lowering the CO2 emitted during transportation as a consequence? Or perhaps choosing a manufacturer that only uses renewable energy would be smarter decision. All this could help make an already established packaging solution even better.

3. Winning here while losing there

3. Winning here while losing there

In the attempts to make packaging more sustainable, we often overdo it, leading to both poor sustainability and poor financial results. The most common mistake is over-thinning the material or choosing a more sustainable but weak material that doesn’t protect the product. If a fragile material is used in e-commerce, then it requires more protective materials to be put in for transportation or even a whole new packaging solution. If the product seeps through a more sustainable packaging, additional bags must be used. The consequences of all these mistakes are similar – changing the packaging or its parts prematurely can lead to the need for extra packaging. This means that we’re taking two steps back by taking one step forward. Another sore subject is unique packaging used chiefly for luxury products to create an original unboxing experience and emotion. It is wrong to assume that by choosing recycled and recyclable materials, a business rids itself of the responsibility to use said materials properly. These types of unique packaging are often made from multiple layers, additional boxes, drawers, ribbons, and other questionable additions. Of course, unique packaging and unboxing experiences that deliver a brands’ message are necessary. But it is worth considering if those brands are not moving in a standard, already established route rather than putting in more effort to surprise their clients by using minimal resources.

4. “Sustainable” packaging – do we really need it?

4. “Sustainable” packaging – do we really need it?

When improving your packaging, it’s good to remember the “R” rules: refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle, rot. We must remember these points to not stagnate with popular solutions while forgetting other possibilities. Let us ask ourselves: aren’t we just shipping air, and can’t our packaging be smaller? Could we make our packaging thinner, simplify its structure, use up the excess materials or optimize the packaging in another way? Relatively simple actions can bring better sustainability results and help save on expenses. Perhaps we can apply the reusable packaging model to particular products or sales models or even remove packaging entirely and allow customers to refill it from the dispenser? In the context of materials becoming more expensive and supply chain incidents becoming more frequent, having this perspective is incredibly important. Let’s not get stuck on only using recycled and/or recyclable materials when we can make significant changes.

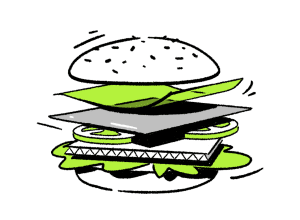

5. Recyclable materials create an “unrecyclable sandwich”

5. Recyclable materials create an “unrecyclable sandwich”

When separate, metal, glass, clean paper, and certain types of plastics can be recycled, but if we glue all of them together, the resulting mess becomes impossible to sort in any standard recycling plant. Despite this, there are instances when such packaging is marked as recyclable, or the subject is left unanswered in communication, with the hopes of it giving the consumer a false sense of sustainability. When combining materials in packaging, one truth is worthy of being remembered – the simpler, the better. If we have packaging made out of plastic, it is not recommended to glue an additional outer layer made from recycled paper so that you can brag about it. This brings zero benefits, and in fact, it only complicates the disposal and recycling of such packaging while further confusing consumers in their attempts to understand which packaging is genuinely sustainable.

6. In pursuit of sustainable fashion

6. In pursuit of sustainable fashion

Packaging made from bamboo, corn, a plant-based plastic, and other solutions are already becoming mainstream. We will not get into detail about which of the solutions mentioned above are wrong or why. But it’s important to note that sustainability depends not only on the materials used but also on the conditions and the means of sourcing, the distance of transportation, the paint, varnish, or other coating materials, and finally on the manner or disposal after use. Often these innovative solutions are put on a pedestal, ignoring the broader picture. Even though certain packaging is made from naturally renewable materials, it can often be improperly recycled due to lack of processing infrastructure. The manufacturing of such packaging may also use up considerably more energy. The materials can be delivered from half a world away, adding to the overall pollution. When you see competitors or packaging manufacturers advertise certain innovations, presenting them as flawless and the most sustainable solutions – do not rush to implement them. Carefully analyze this new solution and ask for comparisons to other alternatives, documentation, or other information that could help you establish the impact that packaging has on the environment, people and other things.

7. Risking the product

7. Risking the product

Continuing with the CO2 topic, this idea might sound controversial, but I think that when creating a majority of packaging for our daily used products, the CO2 part is not as important. While we shouldn’t forget the recycling options, reusability, and potential environmental harm of packaging, it is more important to focus on the preservation and protection of the product within. Why? Because in most products, the actual CO2 trace from the packaging alone is a minuscule percentage compared to that of the CO2 emitted during the product’s manufacturing. Whether it’s cheese or a new phone, these products leave a huge CO2 footprint that is much larger than that of the packaging. Of course, there are exceptions. For example, the beer brand “Carlsberg” in their 2021 account says that their packaging makes up nearly 41 percent of the total product CO2 footprint. The beer itself accounts for 38 percent of CO2 (25 percent for the materials and 13 for the manufacturing). In this example, the brand can clearly identify and improve the footprint of the packaging. But what can we gather from the fact that products we use daily produce significantly more CO2 than the packaging that they are contained in? The purpose and primary goal of packaging are the same as it was for thousands of years from the first archeological discoveries of clay containers – to protect the product and allow for its safe transportation. When creating sustainable packaging, this universal truth is often overlooked, which means risking the product. A damaged product, regardless if it’s a food product or an electronic device, doesn’t only waste a lot of resources but also disappoints the consumer. Of course, there’s no need for overkill. If no products out of a million sustained damages while in transit, that means that they are repackaged, and that damages the environment and raises financial costs. The rule of thumb when searching for a silver lining is that the product’s price should dictate the packaging. Simple and inexpensive products can sustain considerably more damage incidents without compensating for it with environmentally impactful packaging.

8. Harmful marketing and greenwashing

8. Harmful marketing and greenwashing

Marketing is known for embellishments, and when undereducated people are running sustainability marketing, the core of sustainability is in danger of being warped, just like a game of telephone. A poster in one particular restaurant in Vilnius states that their single-use packaging and cutlery “naturally decompose in nature.” This is an excellent example of bad messaging for customers because it creates the notion that it is acceptable to simply leave the packaging in a forest as if it were a leftover piece of apple. This cafe was using packaging meant for compost in an industrial composting setting (we do not yet have a separate waste collection solution, but according to EU legislation, it should be adopted in Europe by 2024) and interpreted the situation differently. Because of these interpretations, which are only used for marketing purposes and bragging rights, businesses cause actual harm to the environment, animals, and humans. The cause of all this is a lack of competence among employees and/or packaging providers/manufacturers. A few years back, one of the many food delivery services active in Lithuania had a separate category called “sustainable packaging,” which was meant for restaurants that used sustainable packaging for their products. However, neither the term “sustainable packaging” nor the criteria on which the packaging was selected were explained. Not only that, but the list contained several doubtful choices: multi-material packaging with an outer layer made from paper, non-recyclable packaging with a “natural-looking” brown print, meaningless symbols that carry ecological messages such as green leaves or circular economy arrows. These things deceive consumers and put a spoke in the wheels of those brands and packaging manufacturers who want to work with sustainable packaging. It’s no surprise that the “sustainable packaging” category has since been removed from the application. But make no mistake, it is important to separate and elevate sustainable packaging, but it has to be done professionally. If you improve your packaging and want to brag about it, do not limit yourself to “environmentally friendly” and “ECO choice” slogans. You can display your achievement on the packaging itself, just don’t forget to provide other critical information or at least a short description of how your packaging should be recycled. For example: “This packaging is recyclable. Recycle with paper. Find more information on the website…”. In retail locations, social media, website, or other channels that reach your customers, you can expand on exactly what, why, and how you did it. Support your logic and include the necessary proof, explain and educate. Your marketing department can always communicate in short and enthusiastic slogans, but it would be a mistake to use them without any supporting arguments.

9. The broader picture of sustainability – ignored

9. The broader picture of sustainability – ignored

The term sustainability doesn’t only include environmental subjects but also social and economic. Suppose the packaging is easier to recycle, but the people manufacturing it are working in poor conditions for below living wages. Can we truly say that we improved the packaging? Of course not. Sustainable growth is possible when environmental and human abundance factors aren’t ignored. Two materials may look identical but be completely different. If we use cardboard, can we be sure that the trees used in its manufacturing will be replanted? If metal is used for metal packaging, will its sourcing impact the scenery and natural biodiversity of the location? Do glass container manufacturers use gas bought from a source that supports conflicts? We can examine a good part of these questions with the help of certifications or by following the environmental systems of those countries, but some topics are incredibly complex, and we need to get to the bottom of them ourselves. It’s not an easy task, but if we want to move towards sustainability, we have to examine our own supply chains.

What is sustainable packaging?

To truly establish the sustainability of packaging, everything is essential: what materials are we using, from where were they sourced and how were they extracted, how, by who, where, for how much and in what conditions is the packaging manufactured, how much resources are being used for transportation, what happens to it after use and what the damage would be if the packaging ends up in nature or some other incorrect location. But it’s impossible to improve every area. During a project like this, it’s essential to ask oneself, “are we doing this to improve the packaging, or are we just creating additional problems?” I recommend using simple logic: improving the packaging in only one area without taking away from other areas. For example, suppose in the past you used only pure plastic and now you’re using 50% recycled plastic, and that doesn’t impede the recycling process or require more energy resources. In that case, the packaging is improving. Of course, it is worthwhile sometimes to question the very concept of the packaging: perhaps instead of increasing the amount of recycled plastic used, it would be better to use a reusable model or create conditions for the consumer to put the product into their own packaging.

Article: Juozas Baranauskas / Illiustrations: Kamilė Korsakaitė / This article is written in order of “Gamtos ateitis” established “Ateities pakuotės” club.

Sources: Eurostat – Recycling rate by type / McKinsey & Company – Performance trade-offs / OECD – waste management and recycling / Lumi – Estimating CO2 / Our World in Data – Food CO2 / Carlsberg Group / Grąžinti verta – Stiklinės pakuotės